In Search of the Ink Immortal

InterviewsIn Search of the Ink Immortal: An Interview with Ian Boyden

Ian Boyden interviewed by Bai Qianshen, Zhang Ping, Hua Rende. November 14, 2011.[1] [2]

[This interview was adapted into an essay titled, 《激情·想象·创造——一位美国艺术家对中国书法元素的感悟与体验》, which translates as "Passion, Imagination, Creativity: An American Artist's Perception of and Experience with Chinese Calligraphy, " and was published in Chinese Calligraphy 《中国书法》 Vol. 4, pp. 104–116 (Beijing: April, 2012). The interview itself first appeared in full in Flowing Movement: The Material Imagination of Ian Boyden (Shanghai: Shanghai Cultural Press (in cooperation with J.Y. Gallery and the Suzhou Museum), 2012.]

Q: So we have a point of departure, tell us what first interested you in Chinese Art.

Ian Boyden: My first interest in Chinese art is what has also proved to be the most enduring one: I am interested in the relationship between ink and paper, how the word can be understood as image and physical form, in the ways the written word can give shape to experience and bring us closer to an understanding of enduring spirit.My first encounter with Chinese art occurred when I was six or seven. I remember the experience very clearly. My parents took me to an exhibition of Chinese calligraphy called “Traces of the Brush” organized by Shen C.Y. Fu. I was totally blown away by what I saw. At that age, I had no idea that I was looking at masterpieces by Wang Xizhi, Huang Tingjian, and Zhao Mengfu. These were names I wouldn't learn for another 15 years. I simply understood that the lines I was looking at did something amazing to me. I often think of art as a mirror in which we get to see ourselves in a new way. I certainly saw myself anew in those pieces of calligraphy. My parents just let me stay in the museum and wander from piece to piece. It was probably the purest exhibition experience in my life and it planted seeds that have endured: my interests in calligraphy, in lines, in word as image, in ink as a material, in paper, in traces of the past, in curating exhibitions—all of these can be traced to that exhibition. So, I give my thanks to Shen Fu, the catalyst for this discussion all these years later. [3]Later in college, I came to China to study at Nanjing University in 1990. I found Chinese calligraphy everywhere: on shop signs, walls, bicycles, menus, and in museums. My memory of that first exhibition came back to me as if I were encountering memories from a previous life. I went out and bought a couple of copy books by Yan Zhenqing and Liu Gongquan and began to study calligraphy. In a letter I wrote to my parents I told them the ubiquity of calligraphy was like I had arrived in heaven, only with a lot of coal dust in the air! I wrote my undergraduate thesis on Chinese calligraphy and in 1995 returned to China to research Chinese calligraphy as inscribed on stone.

Q: In 1995, your received a Watson Fellowship to travel to China to search for stone inscriptions. This is a very unusual thing for a foreigner to have done. Can you tell us about this year, why you wanted to do it?

IB: Of the awards I have received, this is my favorite one. The Watson Fellowship is an unusual grant given each year to a few graduating seniors to travel abroad for one year to pursue a topic of special interest. My proposal was to travel to China to study the history of Chinese calligraphy in relationship to stone. This year of study proved to be a watershed experience: it literally changed my life and deeply informed my artistic practices.During my last year at Wesleyan University, I became fascinated with the kaozheng (考证) movement, especially calligraphers and scholars associated with jinshixue (金石学), like Gu Yanwu, Ruan Yuan, Yi Bingshou, Deng Shiru.[4] I found their calligraphy to be deliberate and strange and archaic. Their calligraphy presented me with an aesthetic that I found very attractive and totally new in the way it articulated the passing of time. In particular, I loved how much their calligraphy retained the memory of stone. So, I wanted to experience these ancient inscriptions myself and see how I would react to them. I somehow knew that the ideas about calligraphy in stone—calligraphy strongly connected to place—could not be conveyed in books. It is one thing to read about a cliff inscription, and quite another to sit at the base of the cliff and feel the carved stone with your own hand. I wanted to feel these inscriptions with my own hands. And I really wanted to see how contemporary calligraphers were reacting to them, and what this aesthetic meant to contemporary calligraphers in China.I wanted to explore these inscriptions because my intuition was that I would find something significant during the journey. We do not have a comparable tradition in the West. Like many of my investigations, I did not begin with a preconceived idea as to what I would find and what I would do with what I found. Instead, I let my year unfold organically, as one inscription led to another.I was very lucky. Before I left for China, Bai Qianshen gave me a letter of introduction to Hua Rende. That letter proved to be pivotal to my experience. I had no idea who Hua Rende was or that he would become one of my most important teachers; that he too was fascinated by ancient inscriptions; that his calligraphy was a powerful expression and transformation of these ancient characters engraved in stone; that he would, in a sense, be my guide through this giant landscape of inscriptions. Ultimately, Hua Rende's calligraphy became a focus of my attention. It was through the lens of his calligraphy that I began to understand the ways that these early inscriptions had shaped the imagination of contemporary calligraphers in China. Ten years later, he and I ended up curating a wonderful exhibition of his work called “Reflections on Forgotten Surfaces: The Calligraphy of Hua Rende.” The Chinese title was Dao zai wa bi (道在瓦甓), after a line from the Zhuangzi 《庄子·知北游》.[5]

Q: Tell us a few of your favorite experiences visiting inscriptions. How did looking at inscriptions change your life and thought?

IB: I'll tell you a funny story that sheds light on that quote from the Zhuangzi. In the autumn of 1995, I climbed Taishan to look at the inscriptions that blanket that mountain. To my delight, there was a herd of goats standing on top of the Diamond Sutra inscription—this is a famous inscription from the Northern Qi and the characters are really gigantic, about 50cm square. The goats were eating little tufts of grass growing from the cracks, and I thought it was great that the Diamond Sutra should be cared for this way. We have a saying in English “you are what you eat,” and I figured these goats were totally enlightened. But then as I was thinking that, one of the goats shit on one of the characters, little pellets bounced over the sutra and some of them rolled into the engraved lines. Somehow this filled me with incredible joy. Not because I thought the goats were disrespectful, but because my understanding of what constituted content shifted dramatically. I knew I was deep in the world of ziran(naturalness). A great line can be simultaneously filled with time, granite, the teachings of the Buddha, and goat shit. The line “The Way can be found in bricks and tiles,” (daozaiwabi) is from the Zhuangzi, chapter “Knowledge Wandered North.” If you keep reading this passage, it ends with the line “The Way can be found in piss and shit!” (在屎溺) And so it was.[6]I am not joking when I tell you this story. You ask how this year changed my life and thought? The year changed the way I understood the act of reading. It is not a big jump from reading words carved in stone to reading the stone itself. And from reading a stone, you can read a pile of stones. You can read the flight of birds, from that the tracks of insects on the bark of a tree, or the track of snails through algae. The whole world is available for the reading. This concept has a long and rich tradition in China—Fuxi reading the tracks of birds, King Yu reading the luoshu[7] and so forth. I carried a lot of books with me on my travels: during one trip to Sichuan, I read Liu Xie's Wenxin Diaolong (The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons). I love that the very first paragraph of the first chapter is devoted to this reading of the world: “The sun and moon, like disks of jade, shed light on the images of the sky. Mountains and rivers in their beauty, unfold the order of the earth. These are the texts of the Way.” (日月疊璧,以垂麗天之象;山川煥綺,以鋪理地之形:此蓋道之文也。)[8]

Q: Did your study of stele affect how you make books?

IB: Yes, in many ways. The most dramatic influence can be seen in my latest set of books that are made out of meteorites. These are objects that formed at the very beginning of our solar system 4.5 billion years ago. Nickel-iron meteorites are filled with Widdmanstätten Patterns, which become visible when the meteorite is etched with acid. When I first saw these patterns, I thought they looked like ancient writing, perhaps Cunneiform, perhaps Chinese, or maybe they were a map to an ancient city. So I decided that I would take a meteorite, cut it into thin slices and then bind it as a book. My invitation is for the audience to read a text from the beginning of the solar system. These are like small hand-held stele, only very, very old. Thoroughly Taoist objects; these are tianshu (天书), or Books of Heaven!

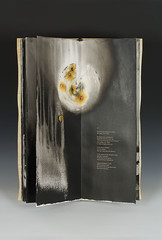

In other ways, the influence of stele was very subtle. The history of the printed word in the west has been dominated by printing the words onto the paper with ink. Thus, the words constitute a material addition to the paper. In China, I discovered rubbings, which are the opposite: the words are white and the surrounding paper is black. So the words represent a material absence. I love the idea that these words are actually composed of air, of the very material that moves through our throats to give them voice. In 2008, I produced a book called Habitations with the American poet Sam Hamill. In this book, I used a laser to engrave his poems into the surfaces of my paintings. I literally removed layers of pigment to reveal the paper below. The effect is extraordinary, and impossible to photograph. To my knowledge this is the first book to ever be “engraved” in this manner. And I consider this idea to be a direct extension of my studies of Chinese stele. In a sense I endowed the paper with the qualities of stone.

Q: How did studying inscriptions influence your sculpture and painting?

IB: In these early inscriptions, there is a spectacular relationship between calligraphy and place. The drive to inscribe words into stones, into the very bones of the earth, I think is a drive to see ourselves in the environment. It is more complex than that. In English we have two words “land” and “landscape.” “Land” refers to land itself, the physical material that you and I see, smell, walk across. . . “Landscape” refers to the ways land occupies our imagination. Related words are “seascape” “moonscape” and so on. These words proliferate with ease. The important thing is that these words describe the product of the imagination actively working on the land (or whatever the subject might be). This can become abstract very quickly, for instance a piece of Chinese calligraphy might be a “word-scape” or an “poem-scape.” What is interesting is that by inscribing a piece of calligraphy into a cliff face, that space suddenly shifts from “land” to “landscape.” Language has fundamentally changed our relationship to the world. The mountain merges with our imagination. The mountain inhabits our imagination, and our imagination inhabits the mountain. As a consequence, I have spent a lot of time seeing how I can relate my work to ideas of dwelling and place.

How did it influence my work? Well, for one, I had to make a stele of my own. My wife, Jennifer Boyden, is a poet. In 2003, she and I collaborated to make a stele called Convergencesfor the City of Walla Walla (Washington State). The stele is made of a single piece of columnar basalt. This stone is over 6 meters tall and about 2.5 meters in circumference, and weighs about 25,000 kg. At eye-level we polished a band around the stone. Jennifer wrote two sets of poetic phrases. In the upper part of the polished stone we inscribed poetic phrases about the sky. These phrases are engraved directly into the stone, so that the words are occupied by air. In the bottom band are poetic phrases about the earth. However, these words are cast in bronze so that the words contain the physicality of metal. These phrases are left unfinished because we want to invite the viewer to finish them for themselves. The polished stone between the two bands looks like a black mirror, and when you stand in front of it, your face is reflected in the stone. The viewer becomes part of the stone, and through reading the text and seeing your reflection, the viewer becomes the agent that connects heaven and earth.Most of the public doesn't know this, but the text is also engraved into the base of the sculpture that is buried underground! This idea also has its roots in Chinese epitaphic stele tradition. And in addition I carved a single eyeball on the top of the stele that would always be looking off into the void.

Q: How do you understand landscape through the lens of calligraphy?

IB: In 1994, I started to study calligraphy with Ch'ang Ch'ung-ho. One day I asked her in what ways she appreciated calligraphy. On that day said, “I like to view calligraphy as a dance, and with a little training I can show you how to see the dance of the brush above a piece of calligraphy.” She wrote the character “小”. And as she did this she exaggerated the hop of the brush from one dot to the other over the central line. She then moved to a piece of her xiaokai, a poem by Jiang Kui. She took a dry brush and we reenacted the dance of the characters. She was very exacting. “It must come from here,” she would say, and kept hitting my shoulder. I understood that calligraphy is intimately tied to body movement. So, when you ask me how I understand landscape through the lens of calligraphy, I think one way is through the ways we ourselves move through landscape. I will tell you a story.

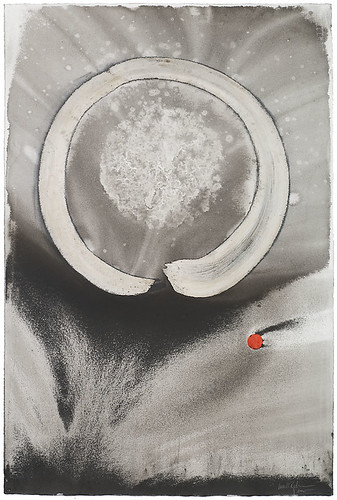

Not all of my climbs in 1995-96 involved me looking for inscriptions. In the spring of 1996, spent about two weeks climbing Wutaishan. I carried a backpack, a sleeping bag, and some food. Some evenings, I slept outside and watched the sky. Other evenings, I was able to sleep in temples along the way. One afternoon, I arrived at a temple on the western terrace. The temple was called Falei Temple (法雷寺). There were only a few monks there. The abbot invited me to spend the night with them. The temple was under repair and giant timbers filled the courtyard. It was cold that night and the monks lent me a robe with sleeves, twice as long as my arms. I wrapped myself in the robe and lay on the timbers, looked at the stars, and listened to the monks chanting. When they finished, the abbot joined me on the timbers and shared stories about himself and his study of Chan Buddhism. I told him about my interest in calligraphy. He told me many monks also loved calligraphy, and then told me about the Tang dynasty Chan monk Nanyang Huizhong (南陽慧忠) and his love of making circles. He loved to write them with a brush on paper, in the dirt, in the air. It is said that Nanyang Huizong had over 90 ways of making a circle. I woke up around 4:30 in the morning and was surprised to find myself all alone. All of the monks were already up and were chanting. I wandered out into a thick fog, wondering how far the sound of chanting of the monks would travel. A herd of wild horses grazing nearby began to walk away as I got closer. When I began to run toward them, they started to run too. We ran around and around the temple, my robe with the long sleeves flapping around like the wings of some strange bird. Finally, out of breath, I stopped running. As I stood there catching my breath, I became aware that the abbot was standing close to me. I looked at him and we both started to laugh. “Isn't it fun to chase the horses through the fog?” he asked. I told him the horse and I were running in great circles around his temple and, in so doing, added one more circle to Nanyang Huizong's list. The abbot laughed and then we ran off into the fog. I think this is probably one of the best pieces of calligraphy I have ever done, when I became a brush in the landscape and in the end left no trace at all.

Q: Your paintings today are meditative and poetic. Some are abstract, and others appear to be landscapes. Do you consider them influenced by Chinese art?

IB: Of course. In many ways my mind has been and continues to be shaped by my experience with Chinese painting and calligraphy. I love process, art which conveys time and sequenced thought. I love wide expanses of blank space (either white or black). I tend to isolate my subjects within the frame of the paper. In my books, I often combine text and image. I associate my work with the literati (文人) tradition of Chinese art, in that I have absolutely no interest in color for color's sake, choosing instead to work monochromatically, and I search for the spirit of the subject in contrast to its outward manifestations. To this end, I have relentlessly pursued the spirit of carbon inks themselves, my hope being to be able to one day make a painting that I think speaks to the spirit of carbon in and of itself. I want this piece to be a symphony, a giant chorus of sorts.

Q: Where else did you visit during your year visiting stele?

IB: I spent the year exploring the landscape of China. In particular, I was drawn to Han, Wei, Jin, Nanbei inscriptions. I used Suzhou as a base and from there I took four major trips.

Trip 1, Suzhou—Qingdao: Kaifeng, Luoyang (Longmen Caves, Kuan Lin, Tomb of Xiaowen, Tomb of Xuanwu, and the Museum of Ancient Tombs), Xin'an, Tiemenzhen, Gong Xian Cave Temple, Tomb of Song Di, Jining (Gallery of Han dynasty stele, Wu Jiaxiang Temple), Qufu (Confucius Temple and Cemetary), Tai'an (Dai Temple, Zhang Qian stele, Heng Fang Stele, Jin Sun Furen Stele), Mount Tai (numerous cliff carvings, Diamond Sutra Valley), Ji'nan, the cliff inscriptions on Tieshan, Yunfeng inscriptions, Penglai, Qingdao, and returned to Shanghai via boat.

Trip 2, Suzhou—Kunming: Zhangjiajie, Wuhan, Three Gorges, Chongqing, Chengdu where I saw the Sanxingdui bronzes, the Han dynasty pillars at Ya'an, Kangding, Litang, Zhongdian, Kunming.

Trip 3, Suzhou—Dunhuang: Xuzhou(Han dynasty tombs of Baiji, Maocun, and Guishan); Xi'an (Lintong Terricotta army, Forest of Stele, Wild Goose Pagoda, Shaanxi Provincial Museum, Yaowang shan, Maoling, Zhaoling, top of Zhaoling), Tianshui Maijishan, Luohe Temple, Gangu, Lanzhou Museum, Binglingsi, Labrang Monestary, Wuwei Daxiangshan, Tiantishan shiku, Zhang Ye, Mati si, Wenshushan shiku, Dunhuang.

Trip 4, Suzhou—Xi'an: Beijing, Datong (Yungang caves, Huayan temple, Hanging Monestary), Wutaishan, Taiyuan (Jinci Temple), Pingyao, , Wutaishan, Taiyuan (Jinci Temple, Longshan Caves), Pingyao.And there were numerous short trips in the Jiangnan region: Yiheming, Nanjing, six dynasties stone animals around Danyang. Q: You said at the beginning of our interview that you think of “art as a mirror in which we get to see ourselves in a new way.” Can you expand on this?

IB: I think this functions in different ways depending on whether you are the maker or the viewer, or in some cases both. There is a famous story involving Huineng. Two disciples were looking at a flag flapping in the wind. One said the wind was moving; the other said the flag was moving. They asked Huineng what he thought. He said, neither, it is your mind that is moving. His observation is jarring and fundamentally important. When I say we see ourselves anew in a piece of art, I am talking about the way that work of art is making our mind move. Sometimes this experience can be very dramatic. For instance, I will never forget my time in the Rothko Chapel (in Houston, Texas) surrounded by Rothko's giant black paintings. The blackness pulsated, fused with the sounds from outside and deconstructed everything I thought I understood about black, and for that matter, everything I thought about chapels. I am thinking about this chapel now, because last week I stood in a room belonging to the master ink maker Hu Lizhi (in Shexian, Anhui Province) specially designed to burn oil for ink. The walls of that room are completely black with soot. As I stood there for a moment I understood that room as another chapel to blackness—this time the blackness of potential and transformation, the residue from the dream of fire. I think the experience is a little different when you are the maker of the work of art. In my case, I am interested in material and process. So instead of the finished work, it is the making itself that becomes a mirror. And it is a complex mirror, because it is a mirror of my own construction. In my own case, I actively invite my materials to inhabit my own imagination so that the process becomes a way for me to see the shape of how these materials inhabit my own mind. In either case, this experience is often extremely private and often unfolds outside the realm of language.

Q: The relationship of father and son is very important in Chinese art history. Your father, Frank Boyden, is a well-known artist. Did you study with your father? How does his work influence you?

IB: Yes, but the method of study is hard to define exactly. What I learned from him was not through classes, but through a way of life. My dad's studio was in our house. Or it might be more accurate to say that our house was in his studio. Everything was covered in clay dust. When I came home from school, I would usually go and sit by my dad while he worked. I learned how to throw pots, I watched him draw. I mixed glazes and washed his brushes. I helped him build kilns and fire his work. I chopped a lot of firewood for the kiln firings. I watched him work a lot, and I noticed how the environment around our house found its way into his work. I grew up in a little estuary on the Oregon coast. Almost all of the subject matter of my father's drawings during that time are of herons and salmon as well as other coastal animals. If I saw a heron spinning in the air, I would also see one spinning across his pots. What I saw around me was having a constant conversation with what I saw in his work. I didn't understand how complex and integrated such a relationship was until much later. Growing up, this relationship of life to work seemed totally natural. Later, I began to see how this environment had become part of my father's imagination. And I have paid close attention to the ways he transformed this experience into lines upon the surfaces of his pots. My father and I have collaborated on several projects over the years, most of them artist books. I have also written and thought about his work quite a lot.[9] I think his work has influenced me most significantly in two ways: one is about material, and the other is about process. When I was young, my father liked to collect his own clay and make his own glazes. He would take me on trips with buckets and shovels and we would go dig up earth and bring it back to his studio. So, from a very early age, I understood the world—not the art supply store—as a source for the raw materials of art making. Later, when I began to make my own paints, I was struck by the fact that the materials that he used for his glazes were more or less the same materials used for paints. The only difference is that the names of the materials are different. My interest in collecting my own materials undoubtedly derives from helping my dad. But it is very different. He wanted to make pots with local material for economic reasons and because in the 1960s and 70s there was a great interest in getting “back to the land” and using local materials. My own search has been about finding materials that inhabit the imagination. The second influence has to do with process. All potters make pots, which then must be fired in a kiln. In my dad's case, he submitted his pots to a very dramatic kiln called an anagama. This is a Japanese kiln that has its roots in the Chinese dragon kilns (龙窑). The kiln is fired with wood and in the process of firing deposits a skin of ash across the surface of the pots, which can be very beautiful. The process of firing a pot in this type of kiln also introduces a great deal of uncertainty into the art making process. There were many times when all the pots in the kiln ended up being ruined. On other occasions every pot was absolutely amazing. The success of the firing depended upon the type of wood used, on the temperature of the kiln, the length of time it was fired, on the weather, and on many, many factors. It was a very dynamic system. In a sense, my father's greatest collaborator is Fire itself. I grew to love the gifts of the fire, and grew to admire my father's love of submitting his work to a material process that was so violent. When I began to develop my own methods of painting, I unconsciously began to submit my paintings to other dynamic material systems. In my case it has been water. I often submit my marks to giant floods of water, submerge them in streams, leave them out in rain storms. And I have slowly begun to learn how to work with the dynamics of water so as to achieve some remarkable effects. The results are oddly similar to the surfaces of wood-fired ceramics.What I learned from my father also presented me with a great challenge. In a sense, I had to learn how to unlearn what I learned from my father so I could better develop as an artist in my own right. I had to find analytical frameworks that would allow me to assess what was truly his vision and what was part of a larger fabric of culture. Our minds, interests, ways of seeing and inhabiting the world, and relationships to materials are very different. He works in Fire and I work in Water. It has been my good fortune to be particularly influenced by the passion my father dedicates to his work—and to understand how I could apply the same passion to develop and cultivate my own style and set of relationships to materials and form.[10]

Q: Could you talk about where you grew up, about your family and how you were influenced by the culture of calligraphy in the Northwest?

IB: I grew up in an estuary on the Oregon coast. It was an incredible environment with many different ecosystems. There was a huge headland to the north called Cascade Head that stuck out into the Pacific Ocean; there were forests with old growth trees and wide-open meadows; there was a river where I loved to fish, and it rained a lot. I spent years exploring this environment. I grew up in a family of artists. As I mentioned my dad is a potter, sculptor, and printmaker. And my mom, Jane Boyden, is a musician. The year I was born, they started a school called Sitka Center for Art and Ecology, which has become a celebrated artist-in-residency program. Growing up, a lot of artists, writers, and musicians would visit us.

The culture of the Pacific Northwest has been especially influenced by Asian culture. This can be seen in artists like Morris Graves, Mark Tobey, Hilda Morris and in the poetry of poets like Sam Hamill and Gary Snyder. I was exposed to their work at a young age. In our own house, we had a giant Japanese scroll of Bodhidharma that haunted one corner. My first teacher was an artist named Margot Voorhies Thompson.[11] She herself had been a student of Lloyd Reynolds, who was a calligrapher and professor at Reed College deeply involved in the revival of italic lettering in the 50s and 60s. Lloyd Reynolds was probably the most important American calligrapher in the 20th century. And Reynold's philosophy was very much a blend of East and West.[12] You know, he was Steve Jobs' teacher, which I guess is why he was so interested in typefaces. Margot was a wonderful teacher. We made nibbed pens out of reeds and quills. She made the art of written forms come alive, introducing us to Western calligraphers like Friederich Neugebauer, Rudolf Koch, Eric Gill, and others. I credit Margot in large part for my interest in lines and ink. I also credit her in part with my love of making my own brushes and other tools.

Q: Your approach to materials and art making is quite philosophical. In recent years, what philosophies or methodologies have influenced you the most?

IB: The ways a work of art emerges from the artist's imagination are mysterious. I am fascinated by how we arrive at making a work of art, or arrive at the appreciation of a piece of art. I read across many disciplines, a lot about neurology and brain function, as well as more speculative works about the nature and function of dreams. In recent years I have spent a lot of time reading the works of French philosopher Gaston Bachelard. He spent much of his life exploring the ways that materials occupy the imagination. He was a great champion of poetry and the poetic image. And his observations about how our imagination gives shape to materials such as air, fire, water, and earth are illuminating. The ways I articulate my art making processes are very much influenced by his thought. I am also interested in dreams and the ways we see and understand materials within our dreams. Bachelard also has much to say about this. As does C.G. Jung. I would not say my work is psychoanalytic in any traditional sense of the word. Instead, I am interested in how we arrive at material understanding and transformation by availing ourselves to the logic of our dreaming selves.This year in China I am hoping to understand how ink occupies the imagination of calligraphers and painters in China. To this end I would be interested in any dreams or thoughts you might have along these lines.

Q: Tell us about your experience at Wesleyan University. When did you start to study Chinese?

IB: When I entered Wesleyan, I wanted to be an archeologist, an interest I still have today. However, to enter the archeology department, you had to pass a French exam. I didn't know French. So I signed up for first-year French. This was just at the time when Wesleyan began to use computers to select classes. I don't know what happened, but instead of getting a French class, I had apparently enrolled myself in first-year Chinese. When I opened the letter telling me my courses for the semester, and I saw first-year Chinese, I thought I must have received someone else's courses. But, no, my name was clearly written on it. I sat under a big elm tree to figure out what to do. I looked down, and to my surprise found a giant praying mantis on the grass looking at me. I showed it my courses and it waved its arms, kind of cheering me on. I decided that perhaps this was fate and that maybe the mantis was my heart in disguise. So I walked across campus and introduced myself to the Chinese teacher, Francis Sheng. I told her my story and about the praying mantis. She said she would love to have me as a student and taught me how to say praying mantis—my first words in Chinese! So I abandoned archeology. The next fall (1990) I was studying at Nanjing University. I ended up with a double major in East Asian Studies and the History of Art. I still don't know French!

Q: For your thesis you organized an exhibition of Chinese calligraphy. Please tell us about that project.

IB: When I returned to Wesleyan in the fall of 1991, I told my advisor, Phillip Wagoner, that I wanted to study Chinese calligraphy and asked whether he knew of anyone I could study with as an independent study class. His eyes lit up and said, “Oh, Yes. You must go find Charles Chu.[13]” And he gave me Charles' phone number. I called him that afternoon and he insisted that I come visit him as soon as I could. The next day I was sitting in his house in New London, Connecticut drinking Qimen tea. Under his guidance, I began to study Chinese calligraphy, both history and practice. He and I took a few trips to Yale and New York to see exhibitions of Chinese calligraphy.In 1993, I decided to curate an exhibition of work by Chinese calligraphers living in America. Charles Chu introduced me to three calligraphers: Chang Ch'ung-ho, Bai Qianshen, and Wang Fangyu. He confided in me that Chang Ch'ung-ho was very special and he hoped she would be my teacher; that he thought Bai Qianshen brilliant and wished he had Qianshen's concentration; and that I should get Wang Fangyu to show me his collection of Bada Shanren. Over the next few months, I went and interviewed all of these calligraphers, and ultimately I curated an exhibition called “The Peripatetic Brush: Four Contemporary Chinese Calligraphers and Their Use of the Past,” which was displayed at Wesleyan University in the spring of 1995. I wrote a catalogue for this exhibition that examined the work of these four calligraphers in the context of tie and jinshixue traditions (The Peripatetic Brush: Four Contemporary Chinese Calligraphers and Their Use of the Past. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University, 1995).[14]

Q: What did you learn from Charles Chu, and where do you think this shows up in your work?

IB: Charles Chu's enthusiasm and joy was infectious. The world unfolded for Charles as a continuous set of marvels, from birds to trees to jiaozi to the erhu to his garden of cilantro and jiucai. Everything was interconnected for him and a source of wonder. Every once in a rare while, you meet someone who you feel you have always known. Charles was one of those people for me. We became very close friends. I say I studied calligraphy with him, but really that was a very small part of it. I traveled to see him once a week for the next four years until I graduated from Wesleyan in 1995. And after that we talked by phone and wrote to each other often until he passed away in 2008. He was like a grandfather to me; I miss him terribly.

Q: You later attended Yale as a graduate student; tell us about that experience.

IB: When I returned from China in 1996, I entered Yale University as a graduate student under Richard Barnhart. I was really excited to have the opportunity to study with him. I think things got off to a good start. I was interested in Dong Qichang and Sikong Tu, and I wrote a couple of long papers considering various aspects of their thought. It is actually amazing now that I think of it, my essay on Dong Qichang was about the ways he articulated the concept of momentum (势 shi). This, of course, has become a central issue in my own paintings. I had a couple of classmates whom I really liked including Susan Huang, who helped me a lot. And I translated a long article by Hua Rende on calligraphy 《論東晉墓誌兼及蘭亭序論辯》, which appeared in an American journal called Early Medieval China.[15]But to tell you the truth, it was during this year that my heart began to shift. It is hard for me to articulate, but I will try. I increasingly knew I was ignoring an essential part of myself that wanted to be an artist. One day, I had a revelation while looking at a painting by the Ming dynasty artist Shen Zhou called Yezuoji (夜坐记) that is in the collection of the National Palace Museum in Taibei. In this painting Shen Zhou sits in a small hut with a candle near him. His essay pours down above him in the sky like a great waterfall of words. In this essay he describes the fluctuations of his mind as he sits quietly through the night. When I appreciate this painting, it is not as an analytical scholar, but as someone who deeply empathizes with the experience. I could very easily place myself in that painting. I asked myself, when people look back 100 or 200 years from now upon my life, what is it that I wanted them to see? At that moment, I knew I wanted it to be something like Shen Zhou's Yezuoji, something that conveys this sense of wonder, of dwelling and habitation, of an active mind, of articulating our experience in words and images. At that time, I did not want my legacy to be that I didn't listen to my own heart and so instead wrote about those who did.

I was writing a lot of poetry at that time, and a bookmaker named Kathy Kuehn expressed interest in making a book with a long 12-part poem called “A Carousel At Birth,” I had written about the Chinese zodiac. We began an intense correspondence about books, book structures, letterforms, papers. Soon I found this correspondence more interesting than my studies at Yale. I visited Chang Ch'ung-ho many times that year, and kept studying Sui dynasty kaishu. And my visits with her were also inspiring. One day I confided my thoughts and doubts to Chang Ch'ung-ho. She told me, “Well, I probably shouldn't say this, but I think what is happening in Art History is mostly empty theory. It has little to do with the actual art itself. And even less to do with living. I am very happy because you are interested in the actual practice of life. If you choose to pursue a life in art, I am sure you will succeed.” So I left Yale and began to make art. Ironically, though, it was my experience at Yale that led me to the kind of art I am most interested in now: art deeply informed by material imagination.

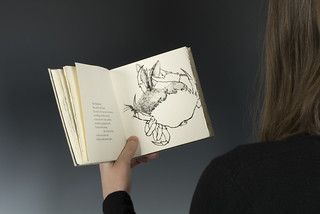

Q: Is this when you founded Crab Quill Press?

IB: Yes. After working for Kathy Kuehn in Portland, Oregon, I started a press of my own called Crab Quill Press, devoted to producing artist books. Many of these books are devoted to the art of calligraphy. One of the first of these books is Peach Blossom Fish that I made with Chang Ch'ung-ho. Chen Xiaowei wrote a beautiful article about this book. I have gained a lot of recognition for my books. They are all handmade and the covers are often made out of beautiful pieces of wood. But it also happens that in America publishing books is no way to make a living. I had to find another job to help support this vision. And that year (1998) an interesting job opened up at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington, to be the Director of the Art Gallery and Curator of their collection of Asian art. I applied for this job and was selected. I held the job for nine years until I finally left to be an independent artist in 2007.

Q: You curated over 70 exhibitions while at Whitman College. What are some of the high points of all of the experiences related to these shows, and why would you classify them that way?

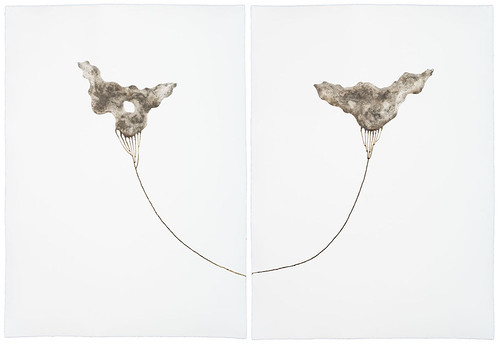

IB: Working in a museum is rewarding. The mission of the museum was to represent all the different departments of the school by programming exhibitions that would dovetail with the curriculum. The programming was weighted toward Asian art, reflecting the museum's collection. I organized exhibitions on many subjects: photography, genetics, climate change, rock ‘n' roll, alchemy, geology. I even built a traditional Japanese teahouse, which became a permanent installation. I am especially proud of two exhibitions. In 2005, I invited Hua Rende to come to Whitman College for a semester to teach courses on Chinese calligraphy. While he was there I organized an exhibition titled “Reflections on Forgotten Surfaces: The Calligraphy of Hua Rende.” For that exhibition, I wrote a book about Hua Rende's calligraphy, relating his calligraphy to the pictorial stones of the Han dynasty.[16] The exhibition was really beautiful. The other exhibition is “Roots of Clouds: Transcendence of Stone,” which I put together in 2006 with Jennifer Boyden and Terry Toedtemeier. This exhibition was very experimental and explored the ways stones inhabit our imagination. For the exhibition catalogue I wrote an essay exploring the relationship of clouds and stones. This essay marked a turning point in the way I think about materials.[17]

Q: This year you are back in China. And once again you are doing something unusual—researching ink. How did you become interested in ink making?IB: My interest actually began in 1996, when I found a Song dynasty ink recipe while studying in the old book room of the Suzhou University Library. The recipe called for pine soot for the pigment and ox hide glue for the binder—two ingredients that alone would make a perfectly good ink. However, the recipe also called for many exotic materials such as musk gland of a deer, ground pearl, cinnabar, sandalwood, etc. Intrigued, I decided to make my own ink by following this recipe. I asked Hua Rende if he wanted to help, but he said it was much easier to simply buy a bottle of ink. I didn't have any idea what I was doing. I spent a few days trying to find all the materials. Then I borrowed a friend's rice cooker. I dumped everything into this rice cooker and added water and began to stir. It did not do what I thought it would do. I guess I thought it should look like mozhi (bottled ink). Chinese love to talk about blacks being luminous and multi-colored and layered. Well, this particular mixture looked like black Hell. But I was having a great time, and I started drinking wine. The next morning, I woke up to find the ink solidified and the rice cooker ruined. Several years later, I met Rich Spelker, an accomplished ink maker, at a workshop being taught by Timothy Ely.[18][19] After we sat on a balcony and watched one of the most incredible storms I have ever seen, I found myself obsessed with finding a way to paint the dynamic motions of rain and clouds. Rich handed me several inks he had made, inks unlike anything I had ever used before. They were sumptuous and commanded my attention. So, I decided once again to make my own inks and paints. My first paint was made with azurite. The handmade paint had a life of its own, the color shifting and shimmering as if it were alive. I had the distinct feeling I was in conversation with the azurite itself. Other materials quickly followed: cinnabar, malachite, lapis lazuli, orpiment, ochres and other colored earths. Each time, the effect was infinitely better than anything I could purchase from the store.

Q: How did these inks and paints affect you as an artist?

IB: I became increasingly intrigued by the ingredients required to make ink. Aside from the pigment and binder, the other materials in the Song dynasty ink recipe appeared to have little function with regard to the physical properties of the ink itself. So little, in fact, that I realized they must be functioning on some other level unrelated to color. Some of the ingredients seemed clearly linked to smell, such as sandalwood, borneol, and deer musk. Animal glues are often stinky, so adding aromatics would not only hide the foul odor of the binder, but perfume the working environment as well. And they might even keep insects away. Other ingredients like cinnabar and ground pearl were much more difficult to understand. With a little research, I found that these materials are fundamental to both Chinese medicine and Chinese alchemy. By adding them to the ink, the ink became a type of medicine and a material invitation to transformation. In addition, carbon black can be derived from any organic material, so why was it important, in this case, that it come from a pine tree—no less a pine tree from Huangshan? Again the answer was not about color, but about symbol and cultural geography. The more I studied, the more complex the webs of influence became. Each ingredient was a way to hold a different kind of conversation with the fuller context of it meaning and origin. How does one carry on a conversation with a forest, a deer, an oyster, and the inside of a mountain? And what does such an act mean? The world of ink can be divided into two categories. In the first category, ink is purely a material for making marks. It is developed and used it for its color (black, red, blue, yellow, etc.) and physical qualities (thick, thin, archival, waterproof, etc.). In this category, ink is something understood to be in the service of our own will. This continues to be the dominant model in ink making, and one that has shaped most of the color pallets for the past 2000 years, not to mention shaping the way we view our relationship to the natural world. The second category of ink is much more elusive and mysterious. In this category, ink is formulated to interact with the user on sophisticated cultural levels in the imagination. The ingredients of these inks are generally multifarious, extremely specific, and often valuable. This kind of ink can be said to be living, to have a spirit. It is the ink beyond ink. This ink contains an invitation to see oneself embedded in and shaped by the world. Adding to its mystery is the fact that these inks only work if you know of their latent powers and are open to their potential influence. I have been deeply rewarded by opening myself to ink's potential. In my case, I discovered that the materials in ink could have a profound effect on my imagination. More importantly, I realized that I was much more interested in what these inks did in my mind than I was in the material's color. Thus, these inks called for a new form of observation. I began to look for materials that had qualities that were linked to ideas and language: to human emotion, culture, philosophical traditions, etc. And, ultimately, began to determine the subjects of my painting.

This framework has changed the way I see the world. If I pick up a stone, I know that I am picking up a story, and I know that it is possible that the story is going to result in a painting. Picking up a stone is therefore the prelude to transformation, not just of the stone, but more importantly of myself. Examples of materials I have used include meteorite dust, freshwater pearls, fossilized shark teeth, opals, various carbons, and a wide variety of minerals, stones and soils from specific geographical locations. Each of these materials has resonated in my imagination.Prior to painting, I spend time studying each of these materials, allowing their stories and characteristics to take root in my own imagination. I pay close attention to their physical structures, how they formed, what their function is or may have been, how they have been used by other people and cultures, what they reveal about distant places and events. Once I have internalized these things, I begin to make paints with the materials and develop painting techniques and compositions specific to each material. And in so doing, I begin a dialogue and collaboration with the material itself. The act of paintings becomes akin to translation, to revealing the image-voice of the other.

Q: How do you see yourself contributing to this ongoing practice of ink?

IB: I think my contribution thus far lies in articulating the fact that the materials of ink have very rich lives within our imagination. But we have to give our imaginations time and space to act upon them. And that if we stop and observe how these materials inhabit our imagination we might be very surprised at what we find and what they give back to our creative process. To my knowledge, I am the first person to make inks of things like fossilized shark teeth, mastodon teeth, and meteorites. I know that these materials are most likely not for everyone, but I hope my material use will encourage people to look at artists' materials in new ways. I see this as way to draw the world closer to me.

Q: How do you think that your perspectives on ink could impact contemporary Chinese calligraphy?

IB: I will tell you my most grandiose idea. I want to start an ink revolution, an ink revival. I want calligraphers to start paying more attention to the inks that they use, because I believe they will find enormous rewards if they do. A few days ago I went to the Suzhou Art Museum with my friend Xu Li to look at a show of bamboo painting. The show contains bamboo paintings of the Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties. We had a great time comparing the ink in these paintings and trying to find language to describe what we saw. The question in my mind is, 200 years from now when people look back at the calligraphy produced today what will they say about the ink? I suspect they will not have a lot of positive things to say. Although carbon black is very black and fine, it is also industrial and one dimensional. It cannot compare with the luminosity and layered inks of the Song dynasty. Contemporary bottled ink cannot engage the imagination in the ways that traditional inks can. Even though I am not Chinese, I think my invitation should appeal to those who understand the knowledge and wisdom contained in traditional materials and processes. Do not let the traditional art of ink making die as China modernizes.This year I have been surprised to find that absolutely every calligrapher I have met uses bottled ink. Asking them why, they all claim that it saves time. I believe the issue regarding time is mostly an illusion, mostly an excuse. You know, it is really only relatively recently that artists have begun to rely entirely on other people to make their inks and paints. And I think that this reliance has created something of a wedge between the artist and the world. It is hard to define what the effects of this wedge are but I think they are more significant than most artists are willing to admit.

Researching the history of Chinese inks, I have found that historically many Chinese calligraphers have loved to make their own ink. This is no accident. Nor was it due to a lack of ink to buy. They simply loved to do it: Li Bai, Huang Tingjian, even emperor Song Huizong. Su Dongpo almost burned down his own house making ink. Others loved to collect ink and some of it was at times even more precious than gold. One of my favorite mornings that I ever spent with Chang Ch'ung-ho, was when she talked at length about her love of using old ink. She brought out many pieces including a beautiful sixteen piece set by Hu Kaiwen that is now in the Seattle Asian Art Museum. These old inks send her into a state of bliss. She talked about the smell of these inks, how rich and fine they were, how they felt in her brush, how using them inspired her. She had a small piece of Ming dynasty ink on her desk—today I really wish I knew who made this ink—and we ground a little of it and I bent over and smelled it. “What do you think,” she asked? It was intoxicating.

[1] Bai Qianshen is a calligrapher and art historian. He is the author of Fu Shan's World.

[2] Many thanks to Zhang Ping for his assistance with this interview. Zhang Ping is a practicing calligrapher, Associate Professor at the Suzhou Institute of Technology, and a member of the Chinese Calligraphy Association. Here is a link to his blog: http://blog.sina.com.cn/u/2362627112. I also thank Zhao Xingtian, Chen Xi, and Teng Fei for their help with translation.

[3] There is a beautiful catalogue for this exhibition that you can still find occasionally: Shen C. Y. Fu, Traces of the Brush. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1977.

[4] An excellent introduction to the kaozheng movement can be found in Benjamin A. Elman, From Philosophy to Philology. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984.

[5] After returning from China, the first exhibition I organized exploring this relationship was "Stone Brushes: Three Calligraphers from Suzhou," which featured works by Chang Ch'ung-ho, Hua Rende, and Wang Xuelei. Contemporary Crafts, Portland, Oregon, 2000.

[6] I am fond of Burton Watson's translation: The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu. New York: Columbia University Press, 1968.

[7] King Yu reading the luoshu on the back of a turtle. There is a particularly delightful discussion of the luoshu in Frank Swetz, The Legacy of the Luoshu. A.K. Peters, 2008.

[8] Read Steven Owen's translation in Readings in Chinese Literary Thought. Cambridge, Harvard University Asia Center, 1996.

[9] I wrote about my collaborations with my father in the book Frank Boyden: Prints & Books (Hallie Ford Museum of Art, 2006) that I co-authored with Prudence Roberts. You can read the essay here.

[10] See Co-Existence with Fire and River Through the Valley of Fire, both published by the American Museum of Ceramic Art. Here's the link to Frank's website: http://frankboydenstudio.com.

[11] Margot Voorhies Thompson's website: http://www.margotvoorhiesthompson.com/

[12] See Lloyd Reynolds, A Life of Forms in Art published by the Douglas F. Cooley Memorial Art Gallery, Reed College.

[13] Here is a delightful site for Charles Chu: http://www.littlefrog.com/

[14] Here's a link to the main essay from the catalogue for that exhibition: The Peripatetic Brush.

[15] “Discussing Eastern Jin Epitaphs in Conjunction with some Notes on Debates Concerning the Orchid Pavilion,” translation of 《論東晉墓誌兼及蘭亭序論辯》 by Hua Rende (华人德), in Early Medieval China 3 (August 1997). Kalamazoo: Western Michigan University.

[16] Reflections on Forgotten Surfaces: The Calligraphy of Hua Rende

. Walla Walla, Washington: Donald H. Sheehan Gallery (Whitman College), 2005.

[17] Roots of Clouds, Transcendence of Stones

. Co-authored with Jennifer Boyden and Terry Toedtemeier. Walla Walla, Washington: Donald H. Sheehan Gallery (Whitman College), 2006.

[18] Richard Spelker is the proprietor of Ootheca Press Laboratory and produces books specially designed to resist bomb blasts.

[19] Tim's website: http://www.timothyely.com/